The rule of law is the cornerstone of constitutional democracy ‚ÄĒ the principle that no one, not even those in power, is above the law. In a democratic nation, it safeguards order, equality, and accountability.

Yet, in an age of political polarization, even the world’s most established democracies are failing to uphold this principle. Leaders, most prominently United States President Donald Trump, have employed tactics to undermine the rule of law, destabilizing the integrity of democracy.

These challenges to the rule of law and the future of liberal democracy took center stage Tuesday (Oct. 21) at the fifth-annual Stanfield Conversation at H¬ĢĽ≠. This year‚Äôs panel welcomed two bright minds in the world of law and political science: Asha Rangappa, former FBI special agent and senior lecturer at Yale‚Äôs Jackon School of Global Affairs, and Wayne MacKay, professor emeritus of law at Dal‚Äôs Schulich School of Law.¬†

L-R: Mary Lynk, Wayne MacKay, and Asha Rangappa.

Mary Lynk, journalist and producer of CBC’s IDEAS and this year’s guest moderator, didn’t shy away from addressing the elephant in the room: just how worried should we be?

Here are some key takeaways from the conversation. Watch a full video of the conversation at the bottom of this article.

What happens when the bulwarks fail?

Experts warn that the defensive walls meant to protect democracy ‚ÄĒ the ‚Äúbulwarks‚ÄĚ ‚ÄĒ are showing cracks.

In the U.S., those safeguards include federalism, the balance between states and the federal government, and the division of military authority between Congress and the President. These mechanisms are designed to maintain checks and balances, preventing any one branch from dominating the others.

But according to Rangappa, those systems depend on something less tangible: trust.

‚ÄúAll of these should be operating in a way that should prevent what‚Äôs happening from unfolding,‚ÄĚ she says. ‚ÄúBut as things start to go south, often the operation of government rests on norms, and not formal rules or laws.‚ÄĚ

For centuries, democracy has functioned on the assumption that leaders will act in goodwill even when not legally compelled to do so. That assumption, Rangappa argues, no longer holds.

‚ÄúWhat we are discovering is that perhaps in today‚Äôs climate, norms are not enough. Norms work when there is trust. When trust breaks down, then you need more formal structures in order to keep people honest.‚ÄĚ

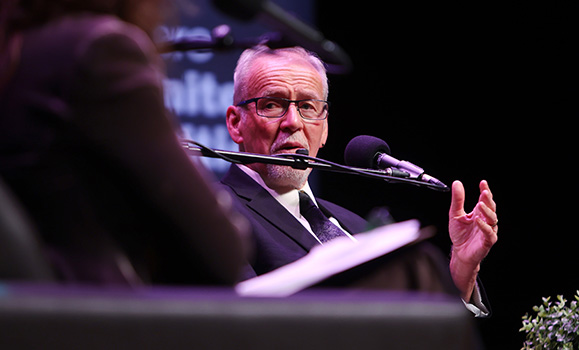

Wayne MacKay.

MacKay echoed the concern, expressing that social media has eroded expectations that once held government together.

‚ÄúWe assume people will follow these, but clearly that‚Äôs not happening in lots of places, certainly not in the United States,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúCanada has some of its own issues in that regard. Things that have worked in the past to protect us may not do quite so well in the future.‚ÄĚ

Both agreed laws alone cannot save democracy. Democracies depend on shared trust and good behaviour, so when that trust and accountability fade, even the strongest institutions can falter.

Power in one set of hands

Power in the U.S. is becoming dangerously centralized, eroding the traditional processes that keep the rule of law and democracy stable. At the heart of this shift is the ‚Äúunitary executive,‚ÄĚ based on an interpretation of the U.S. Constitution that claims all executive power is vested in a singular person: the president.¬†

As Rangappa concedes, the president cannot feasibly do everything himself. Therefore, under his view, everyone in the executive branch is ‚Äúeffectively his mini-mes, there to effectuate his will.‚ÄĚ What this means is that he can hire and fire people at will.¬†

‚ÄúIt‚Äôs now understood by this administration and many in the court to mean there‚Äôs no daylight between him and the Justice Department,‚ÄĚ Rangappa says. ‚ÄúIn other words, there‚Äôs no independent Justice Department.‚ÄĚ

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court‚Äôs ‚Äúshadow docket‚ÄĚ ‚ÄĒ a process where major decisions are made quickly, often without full hearing or explanations ‚ÄĒ has raised concerns about transparency and accountability.¬†

The result is a steady erosion of democratic norms as decisions once made through open deliberation increasingly occur behind closed doors. Together, these trends suggest reducing oversight, making it more difficult for the public to hold power accountable.

A different America: the threat of the Insurrection Act

The line between military power and civilian life is blurring, raising questions about how far the president may go to hold onto authority.

At the center of this concern is the Insurrection Act which, according to Lynk, is considered one of the ‚Äúmost dangerous laws in America‚ÄĚ as it effectively allows the president to utilise the armed forces to engage in domestic law enforcement.¬†¬†

Mary Lynk.

However, under the wrong power, this can be exploited for political purposes.

Rangappa fears that invoking the Act could be used not just to enforce authority, but to normalize military presence and law enforcement on U.S. streets as a tactic to influence elections by intimidating voters.

‚ÄúI think part of the endgame is to get people normalized to the idea of having federal forces on the street,‚ÄĚ she says. ‚ÄúYou can make it harder to vote by mail, so you force people to turn out. If they turn out, you can arrest them. [By then], you‚Äôve already missed your chance to vote.‚ÄĚ

For ordinary citizens, frequent sightings of troops in camouflage and armed patrols could start to feel routine. This political control, she argues, is what the erosion of democracy will look like.

Public denial and complacency in a realm of misinformation

‚ÄúThere are people who don‚Äôt want to confront reality,‚ÄĚ Rangappa says. With language like authoritarianism and fascism floating around, people find it hard to believe because ‚Äúthis isn‚Äôt Germany 1939. It still looks normal.‚ÄĚ

However, she assures the audience, ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs not the threat of authoritarianism; we are on the path.‚ÄĚ

To which MacKay says, ‚Äúnobody can be complacent.‚ÄĚ Through a Canadian lens, he says, ‚ÄúIf you are complacent and not paying attention to what‚Äôs happening elsewhere and think it can‚Äôt happen here, you‚Äôre likely to have an unpleasant surprise.‚Ä̬†¬†

However, despite this period of darkness, both experts still have hope.

To safeguard democracy, MacKay urges citizens to be more engaged.

Channeling the words of Martin Luther King Jr., he says, ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs not so much the actions of bad people who are cruel and abusive, but the actions of good people who say nothing about that.‚ÄĚ

Attendees line up to ask questions.

Attendees listen to the conversation.

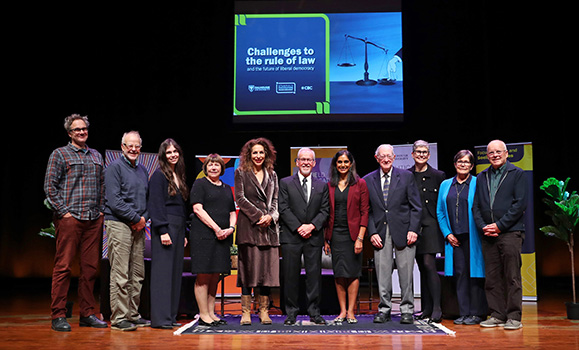

Event organizers and panelists.

The Rebecca Cohn Auditorium was packed for the fifth-annual Stanfield Conversation.

Now, watch the full event

Full video of the 2025 Stanfield Conversation below and .